This week’s murder is not a murder.

Execution is state-sanctioned homicide, the deliberate taking of a life to atone for a crime. I tend to work on a period (from the 1840s onward) where death was the punishment for only a handful of crimes, only likely to be carried out on convicted murderers, and where the state were increasingly likely to be merciful.

But it wasn’t always quite such a last resort. Homosexual sex was a capital crime until 1861, although the death sentence was a mere formality, with a reprieve granted almost as soon as the prisoner left the dock from the 1830s onward.

Today’s story is very local to me, based in Stamford, Empingham and my own Peterborough. It’s a story I’ve told before, although since I last wrote about it in 2019, a much better source for the trial has been digitised.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Catherine Clarke, a descendent of today’s subject, who graciously and generously shared her research with me this week. You can read her write-up of this story here. Thank you again, Catherine.

This is a story of the majesty - and the horror - of the law.

David Thompson Myers was born in Haile in Cumbria in 1771. His father, also David, was the local vicar. While David was still a small child, the family relocated to Greatford near Stamford. Francis Willis, physician to George III, lived at Greatford Hall and Reverend Myers would have been his neighbour and vicar until his early death in 1780. It’s not clear whether these family connections helped David, but he did well enough for himself.

On 2nd May 1799, at St Mary the Great church in Cambridge, David married Phoebe Crow. Phoebe was three years younger than David and was baptised in Wilburton. They moved to Stamford, where David ran a drapery shop on Ironmonger Street. Phoebe worked alongside him, visiting London to choose fabrics. In 1808, David was declared bankrupt, but the business carried on regardless in Phoebe’s name, although it moved to St Paul’s Street. Adverts for Mrs Myers’ fashionable millinery filled the local press.

The birth spacing of their children suggests the Myers had a reasonably active sex life. Charles was born fifteen months after the wedding. George was born in 1802, William in 1804, Caroline in 1805, Lucy in 1807 (she died in 1809), Hannah in 1809 and finally, Henry, in early 1811.

But David was not a heterosexual man.

In a world where gay sex was a capital crime, men had to be careful in their arrangements. Rumours floated around Stamford about David’s preferences for years before he was caught out. His bankruptcy may have been poor business dealings, or it may have been from paying blackmailers.

Christmas 1810, and Phoebe was about a month from giving birth. Thomas Crow was around sixteen years old, and probably her brother or nephew. He was apprenticed to a tailor in Stamford, and he spent a lot of time with the Myers family.

On the Sunday after Christmas, the 30th December, on a snowy afternoon, Thomas and David walked to Empingham to visit the White Horse. David gave the landlord a false name. From here, they went to the Black Horse (pub names being rather limited in Empingham), and then back to Stamford. They arrived in town at 6pm, by which time it was dark, and the two men were rather drunk.

When they got back to Stamford, David asked Thomas to hang around while he checked his wife was out - she was at chapel, the house was empty. Then he asked Thomas up to the bedroom. Thomas said he kept it quiet because David promised to do great things for him. According to Thomas, he had sex with David at least three times over the Christmas period.

In July 1811, a local upholster named Thomas Snow beat the crap out of David. This was no pub brawl: Snow’s attack was very serious. However, this case never came to court. Had David propositioned Snow? Or perhaps one of his apprentices? It’s impossible to know. However, in September 1811, the corporation of Stamford got to hear about Thomas and David’s relationship, and although it’s not entirely clear how, the timing suggests that it emerged from the Snow assault case. The corporation raised a prosecution against David, and he was arrested and remanded in Lincoln castle prison.

He was tried at Lincoln assize on 11th March 1812, on three counts of sodomy. The first count was dismissed because Thomas could not remember the date it had occurred. Several witnesses engaged in tailoring in Stamford testified to the ‘base’ nature of Thomas Crow, and to his habits of petty theft and lying. The jury found David not guilty on the second count, from the 29th December. The third count, also concerning Thomas Crow, was dismissed.

David went free.

And was immediately arrested again for a fourth offence. The fourth offence took place on Burghley Park, which meant it took place in the Liberty of Peterborough. Peterborough was a bit of a legal anomaly in the nineteenth century in that it had the right of oyer and terminer. This meant that the court in Peterborough could try felony crime committed within the Liberty. The Lord Paramount of the Liberty was the Marquess of Exeter… and it was his park that David had used for sex, his back garden. By the middle of the century, the magistrates of Peterborough sent capital crimes to be tried at Northampton assizes, but in 1812, there was no such compunction. This was personal.

His trial took place at Peterborough on 8th April, in front of the magistrates. A jury was summoned from the Liberty. The jury were men that David knew, that he’d done business with.

Thomas Crow told the magistrates that in the spring of 1811, on several occasions, he had gone to Burghley Park with David for sex. Burghley Park was a good choice for covert sex: lots of tree cover, easily accessible, several exits. On one occasion, they left the park separately, but were seen by Thomas’ master, Mr Horden. Mr Horden confirmed this in court.

And despite the previous case being thrown out at Lincoln assize, and despite Thomas Crow’s evident bad character, the jury found David guilty of sodomy.

The death sentence was passed. David was horror-struck.

The execution was expected to take place a week after the verdict, but this family had connections, and David’s uncle (a magistrate and vicar himself) appealed directly to the Prince Regent for help. But the Regent refused to intervene, and the Secretary of State said:

“that offended Justice must inevitably strike its mortal blow, against an abomination of so hideous description”

David’s execution was fixed for May 4th. He spent his last weeks living in the tiny cathedral prison, a couple of subterranean rooms by the main gatehouse, used as shops in my lifetime.

David said goodbye to Phoebe on 30th April. He declined to attend the execution sermon held at the cathedral on May 3rd, although most of the town attended either that service or its mirror at St John’s over the road. Instead, he was given a private sacrament, and attended by Reverend Pratt of Paston.

David’s coffin was placed in his cell on night of the 3rd. Who knows if he slept? The next morning, he waved to the crowds gathered in the cathedral precincts as he waited to die.

The site of David’s execution is often reported as being on Butcher’s Piece in Fengate. In 1899, Thomas White Holdich told the press that he attened David’s execution on North Bank. This was faithfully reproduced by Andrew Percival in his book on Peterborough, published in 1905. Andrew was a solicitor in the town, and one of the coroners during my thesis period. Andrew was born in 1818 and came to Peterborough in 1833, long after the last execution. His father in law, John Gates - another coroner -was 26 when David was executed, and must have mentioned it to Andrew, in either personal conversation or while training him as a solicitor. But Andrew does not mention the case in his book. Thomas White Holdich, our only eyewitness, was two and a half years old when David was executed and perhaps not a reliable witness.

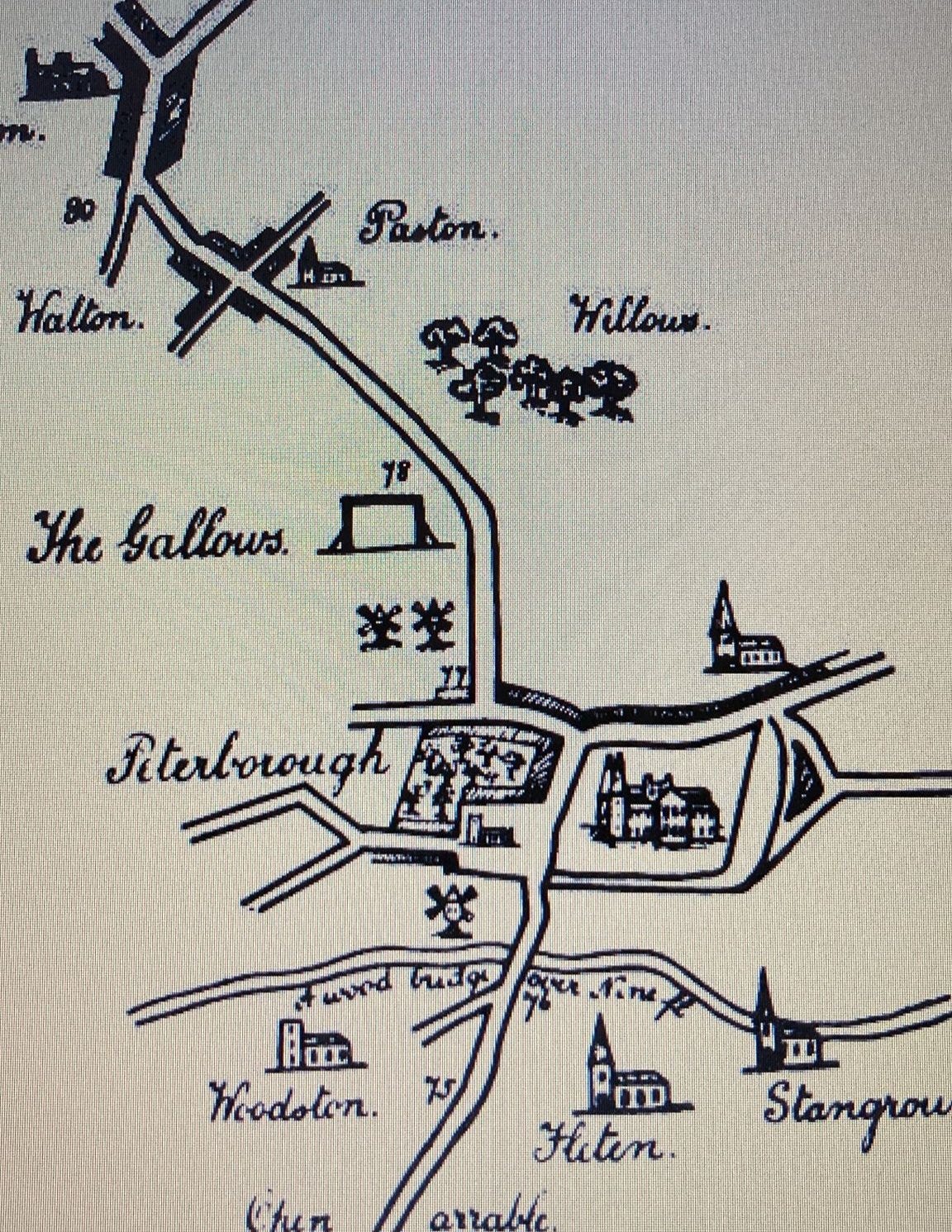

Typically, executions were held on the gaol where the prisoner was held, up high so the crowd could see. But Peterborough’s gaol was within the cathedral precincts and spilling blood on consecrated ground was taboo. According to coaching maps of the London to Lincoln coach route, published in the late 18th century, the gallows at Peterborough were sited just beyond Millfield, at a mile point that is now one side of the Triangle:

It is not impossible that there was more than one execution site, although a town the size of Peterborough did not really need two. I find this contemporary illustration of the gallows more compelling evidence than hearsay reported some ninety years after the event.

However, wherever it took place, the accounts of David’s execution are clear. He travelled half an hour by chaise to ‘the usual place of execution’, and there were thousands of people there to watch. The scaffold was newly built, and he ascended calmly, bidding a small child he knew farewell.

He confessed his crime on the scaffold, a nightcap was pulled over his face. He spat out the orange he’d been eating and said:

“Now is my last curtain drawn”

The bolt was pulled out, and David was strangled.

He left a confession to be printed in the paper, and it was widely disseminated. He was spared dissection, and buried in Cowgate cemetery with a letter from his wife on his chest, in a vault with space for his wife to join him on her death.

Phoebe Myers survived her husband by forty-eight years. She never remarried. Indeed, she used his death to drum up some custom:

David’s uncle started a subscription to provide for her, and she did well for herself, as did her six surviving children. She ended her days living in the very lovely Rutland Terrace in Stamford. But she was not buried with David: her grave is in Flintham, where her eldest son was the incumbent vicar.

For twelve years, rumours about David’s sexual preference were gossip in Stamford, even as his wife delivered baby after baby. This suggests that David was not very discreet, but gossip is not admissable as evidence. It’s not clear why, some months after this relationship had ended, Thomas Crow chose to go to the authorities about his relationship with David, risking being indicted himself. I suspect blackmail, but it’s also possible that he was simply spurned.

David and Thomas’ relationship was uneven; there was a power imbalance there, one we’d perhaps recognise as grooming today. David was old enough to be Thomas’ father, Thomas was only about sixteen when the acts took place. David’s promises to get Thomas work and money in exchange for keeping quiet about the sex were manipulative, but having sex with him at all was dangerous… as Thomas demonstrated less than a year later. David perhaps chose to seduce him because he thought Thomas wouldn’t be taken seriously in court. After all, Thomas could not have been David’s first sexual partner - perhaps he was merely the last in a string of apprentices; young, poorly resourced, easily manipulated, and likely to leave town within a few years.

Thomas was not considered a very reliable witness, which is why the Lincoln prosecutions failed. But Peterborough was a very different matter. Everyone involved knew each other. The magistrates knew the prosecution and defence solicitors very well: the legal fraternity of Peterborough was tiny and overlapped considerably with Stamford. The jury (if they were similar in profile to coroner juries) would know David and Mr Horden, Thomas’ master. They would also have heard the rumours themselves, something less likely for the jury in Lincoln.

I believe that, if the fourth indictment had taken place anywhere other than Burghley Park, or if the case had been tried at Northampton assizes, David would have been acquitted.

But let us not lose sight, amid the legal peculiarities, the horrific reality.

David was killed by the state for having sex.

David Thompson Myers

(1771-1812)