It’s an AGE since I did a talk, and I’ve got two coming up in the next few months. The first is on 18th June ONLINE, for Curious Histories, and will cover a history of the inquest with case studies from Brighton.

The second is on 19th AUGUST and is that rarest of beasts, IN PERSON, at Peterborough Museum. I’ve spent the last few months helping put an exhibition together on Peterborough’s railways, and the talk is about the railway death… but also about life, and community, and leisure and working patterns. You can buy tickets here.

On to this week’s murder, a tale of revenge in Todmorden.

Reverend Antony John Plow was born in Greenwich in March 1831, son of a genteel clergyman who ran a school. He was well educated and went to Cambridge to study theology. He left in 1855, and was ordained a year later. After a few years of moving around, he became the vicar of St Mary’s in Todmorden in Lancashire in 1863. He married Harriet Louisa Bridges in 1864. She was the sister of poet laureate Robert Seymour Bridges, stepdaughter of John Molesworth the vicar of Rochdale, and granddaughter of a 4th baronet Affleck. Two children were born - Antony in 1865 and Mary in 1866 - and by late 1867, Harriet was expecting a third child.

They had help, of course. They employed Jane Smith as a nurserymaid, along with two other domestic servants: Mary Hodson and Sarah Elizabeth Bell. Sarah was born in Maunby, but moved to South Otterington with her parents in the 1850s. She was only just fourteen when she moved sixty miles across the country to work for the Plows, in November 1864.

Miles Weatherill was born in Langfield, just outside Todmorden, in February 1845. His father was rumoured to be an abusive man, but he died when Miles was five. His only surviving sibling, a sister, was a baby at the time. His mother, Alice, did her best to keep the house together, taking in lodgers and working as a cleaner. Miles went to the Wesleyan chapel school, and was said to be a good grammarian. However, like most youths in Calderdale, he went to work in the textile mills as soon as he was old enough.

Miles started attending St Mary’s church and Sunday School, after Sarah Bell caught his eye. He was under the impression that she was close to his age (twenty-one) and was determined to do the right thing. So, in early 1867, he paid Rev Plow a visit, hanging around after church, and asked permission to court Sarah.

Reverend Plow was relatively young (35), and newly married. He was well aware of the temptations of the flesh, but told Miles that Sarah was only sixteen and even if she’d been older, he was unwilling to allow a long engagement while Sarah was in his employment. He thanked Miles for his honesty, congratulated him on his courage. But he would not allow Miles in the house. He would not allow Sarah to walk out with him.

He said no.

Harriet Plow had spoken to Sarah about Miles. Sarah told her that she wasn’t really interested in Miles, and Harriet told Antony that “Sarah will not have a weaver”.

Around this time, Sarah was promoted to household cook, which meant a pay increase, a bit more prestige within the household, and slightly better working conditions. Miles continued to court her. He started visiting her at the parsonage when the Plows were in church (a nice reliable timetable!) and if Sarah had been uninterested to begin with, she was now fully invested in this relationship.

In September, Antony Plow summoned Sarah and reprimanded her (‘carpetted’ her, in the slang of the time) for continuing to meet Miles and lying about it. Jane Smith had grassed Sarah and Miles up. It seems that the Plows gave Sarah a fairly lengthy notice period, but there was an almighty row on 29th October, and Sarah was dismissed. She left on 1st November. Elizabeth Spinks was hired to replace her.

Sarah went to see her mother in Kirby Miske, and Miles went with her. He stayed with her for three days and went back to Todmorden. Sarah went to work for a vicar in Middlesbrough but left before Christmas. She then went to The Retreat at Lamel Hill near York, a Quaker-run asylum. She did not see Miles for five months after leaving Todmorden, although they wrote to each other regularly.

On 10th November, Miles went to the Plows and had a row with Harriet. The references given to servants by old employers (their ‘character’) was absolutely vital in securing new employment. Harriet had given Sarah an honest character: she said that Sarah had left because of a breakdown in trust. Miles came back the same afternoon and had a shouting match with Antony, but Antony was in a holy rage at this upstart youth upsetting his pregnant wife. He told Miles he was a blasphemer, that Sarah had lost her respectability and that they were both unChristian.

Miles swore to have revenge. The focus of his ire was Jane Smith. In letters, he called her a traitor and begged Sarah to come back to Todmorden so they could annoy the Plows by walking out together. She told him to leave it alone, and wouldn’t come back. Odd things happened at the parsonage: windows were broken, pistol shots were heard, and Antony sometimes heard a strange whistling. He does not appear to have reported this to the police.

On 7th February 1868, Harriet Plow gave birth to her third child. The birth was difficult, the baby unhealthy. It’s likely that Harriet was already suffering from tuberculosis, which was rife in that part of the world regardless of economic status.

On 1st March 1868, a Sunday, Miles went to The Retreat to see Sarah. He met her in the morning and asked to meet up privately. Sarah snuck out at 2am to see him. They had an argument: Sarah enjoyed her life and work at The Retreat and refused to come back to Todmorden. They returned each others’ love letters, and Miles gave her a locket and asked her to wear it and think of him. According to Sarah, they parted as friends.

But Miles was boiling with rage.

He went home to Todmorden and made several purchases. He bought an axe. He bought four pistols. He made a makeshift gun carrier from a belt, tied it under his shirt, and went for a drink of whisky.

Then he went to the parsonage. He arrived around 10pm. Harriet Plow had gone to bed, Antony was in his study, the servants were finishing up their wash day. The servants heard a noise, and fetched Antony. Antony found the back door would not open, so he went to the front door. There, he was confronted with Miles and his axe. Miles shot Antony, but the gun failed to go off. They struggled to the back door, and the servants opened it.

Miles and Antony pushed into the passage. Miles hit Antony in the face and head with the axe. Elizabeth Spinks ran up behind the pair and grabbed Miles by the hair to try and get him off. Miles put a gun to Antony’s head and fired, but again, it failed to go off. Jane tried to help, but Miles hit her with the axe, almost severing her hand. He then hit her repeatedly over the head. She crawled away and shut herself in the dining room. The axe was dropped, and Mary Hodson took it away. Antony left the house to get help. Elizabeth had not seen the guns, and believed Miles was unarmed without the axe.

One of the pistols had fallen to the floor, and Miles smiled, picked it up and went into the dining room. He shot Jane in the head, twice, at point blank range. Elizabeth heard the shot, and ran out of the house to find help.

But Miles had not finished. Left alone in the house, he went upstairs to where Harriet laid ill in bed. The monthly nurse, appointed to look after Harriet and the baby in their recovery, had been sent to the landing to see what all the noise was about, and witnessed the attack. She saw Miles reloading the pistol, and went back into the bedroom. Miles came to the door, and the monthly nurse begged for mercy.

Do not hurt the newborn babe!

But then someone knocked at the door, and the monthly nurse went to open it. While she was gone, Miles went into the bedroom and shot Harriet. Once again, the gun failed to go off properly although he tried to set fire to the bed. He attacked her with a poker, causing dreadful injuries to her face and neck.

Miles was arrested before midnight. Jane was dead, Harriet was thought likely to die and Antony was walking wounded.

Miles was present at the inquest, held at the Queen’s Hotel on 4th March, right next to the parsonage. The coroner was John Molesworth, son of the vicar of Rochdale and stepbrother of Harriet. At the close, Miles said:

“The worst has come to the worst. Had Mr Plow given me the privilege I once asked of him, I should now have been a religious and devout Christian, a teacher in the Sunday School, and a communicant in the church, for I would never have partaken of that holy feast to make a mock of it. I should have now been on my way to heaven instead of destruction. I hope Mr and Mrs Plow will forgive me and that God will.”

And then he sobbed.

Miles went to the magistrate’s court twice before being indicted for murder. He took copious notes, and questioned the witnesses, particularly Antony Plow, closely but to no apparent purpose. There was no doubt that he had done it. His questioning seemed designed to try and prove he had been provoked, that the Plows had been unfair to Sarah. Sarah gave evidence at the magistrate’s court too, and seemed keen to distance herself from the whole affair. However, after the court closed, they had an ‘affectionate interview’.

Miles was sent to await trial at Manchester on 6th March, and Jane was buried on the same day. Her funeral was presided over by Antony’s father, Henry Plow.

On 12th March, a double tragedy hit the Plows. Antony died, after developing meningitis. And so did baby Hilda, who was barely a month old. She was unharmed in the initial attack, but already frail and removed from her mother’s care into the care of the coroner (Harriet’s stepbrother), she died quickly. The coroner then refused to allow reporters to attend Antony’s inquest, which was an unpopular decision: he seems to have considered holding such an inquiry on the body of a man of the church, his own brother-in-law, unsavory and unnecessary. A second verdict of wilful murder against Miles was returned anyway. No proceedings were held for little Hilda.

Miles was tried for Jane’s murder at Manchester at 9:30am on 13th March, just twelve days after the attack. The assize was a busy one, with thirteen homicides. Four were found guilty and sentenced to death, including Miles. At the magistrate’s court, he had talked and talked but when the death sentence was passed, he said nothing. An attempt was made to raise a petition to reprieve him on grounds of insanity - his mother’s stupidity and his little sister’s learning disabilities were used to demonstrate a familial weak intellect - but they failed.

Miles was unrepentant. His mother and Sarah visited him on his last night on Earth, and he became ‘lively with grief’.

He was one of the last people to be publically executed in England. On April 4th 1868, Miles, along with Timothy Flaherty, was taken to a scaffold at the front of the New Bailey on Stanley Street in Salford. This prison, demolished in 1871, was replaced by a railway goods yard and is now commemorated as New Bailey Street. The crowd was so thick, and assembled so early in the morning, that they’d woken Miles up at 2am. There were concerns that there would be riots, following the execution of the Manchester Martyrs the previous November, but nothing untoward happened.

The two men died badly, according to one reporter. They ‘struggled considerably, and the length of time they were before the public before expiring was unusually long' The long-drop method of hanging, which generally provided a clean and quick death, was still four years away. Other newspapers reported the deaths were unremarkable.

Miles was buried within the prison walls.

Miles was an unusual murderer. Instead of killing his girlfriend, he killed everyone who he percieved had wronged her. Jane Smith was his main target, alongside the Plows. He left the other servants alone, seeing them as innocent, but he was an avenging angel of death. If he’d killed Sarah, it’s likely that he would have been found insane. But he killed a very high-profile local family.

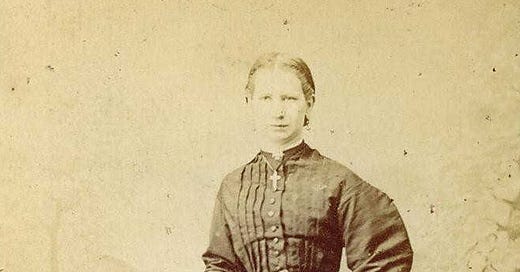

Jane is barely mentioned in the newspaper reports of the deaths. They give her no biography. She was born in Bedale in 1842, but that’s all that is known. The Plow and the Molesworth families dominated her death, down to ordering her coffin be made to Henry Plow’s specifications. A photo of her survives, taken by a service registry in Todmorden:

This was no domestic murder. This was a home invasion, an armed attack, that crossed class boundaries and horrified the local elites. Miles was not tried for Antony’s murder, but it was the attack on the Plows that made him so dangerous, not the attack on Jane.

Despite their fortune and status, life did not improve for the Plows. Harriet took her children to live in Wantage after the murders. Little Antony died seven months after his father, from meningitis. His mother died on 19th March 1869, just over a year after the murders, from tuberculosis. Mary, who was not quite two years old at the time of the attack, was the sole Plow survivor. She went to boarding school, before marrying a vicar. She died in 1952, aged eighty-six.

John Molesworth, Harriet’s stepbrother and the coroner at Jane and Antony’s inquests, is the great-great-grandfather of the Duchess of Edinburgh.

Miles’ sister, Sarah Ann, may have been widely claimed to be an idiot, but married in 1877. She moved to Whaplode Drove in the bowels of Lincolnshire, with her mother. Alice Weatherill returned to Todmorden to die in mid-1881, and Sarah died in Whaplode in 1924.

Sarah Elizabeth Bell is untraceable after the trial.

Jane Smith

(1842-1868)

Antony John Plow

(1831-1868)

Hilda Elizabeth Plow

(1868-1868)

I wrote about this case in my book Volume 1 Bloody Yorkshire.