This week, I actually started writing my thesis. It’s an incredibly odd sensation, after spending three and a half years thinking about what I might write, to actually put words down. I’ve given myself a very long time to write up, including a few more bits of research to do… but I’ve done 1000 words so far. Only 99000 to go.

I’ve also written about one of the weirdest deaths in my whole dataset. Adelaide Bassett was an aeronaut who fell from the sky over Oundle Road in 1895.

This week’s murder took place in the slums of Ardwick in Manchester, in 1871, and is a study in inhumanity.

Catherine O’Brien, as her name suggests, was born in Ireland, probably in 1820. We don’t know where she was born, or when she came to England, only that she ended up in Manchester, with her weaving parents. She was living in the city by 20th December 1840, when she married George Armitage at the cathedral in Manchester. He was also a weaver, as was Catherine.

We know they still lived in Manchester, on Irk Street, in 1841 and that they still lived there when their son was born in 1842. George appears to have died between 1842 and 1847, possibly in Huddersfield. If so, Catherine returned to Manchester, where her little boy died in 1847.

Catherine was now twenty-seven. She’d lost her husband and her only child and although she could support herself well enough in textile work, she was perhaps looking to settle down. Enter George Ellis. George was younger than Catherine, born in Manchester in 1828. He was the son of a house painter, and worked as a carter, probably on the railway - Manchester was full of goods stations, which required men to transfer goods from road to rail and vice versa.

On 1st October 1848, they married at Manchester cathedral. According to their marriage certificate, Catherine was 28, George was 21 and they lived together on Nicholas Street. George could sign his name, Catherine could not.

They appear to have struggled in their early marriage, and were lodging in a yard off Deansgate when the census was taken in 1851. Their first baby - George - was born soon after this census, followed by Thomas in 1853, William in 1857 and John in early 1861. By the time John was born, they lived alongside the Central station, and George worked as a porter. There were three different stations in the area: Central, Cheshire Lines Goods and the Great Northern Goods, and George could have worked for any of them. Catherine continued to work in the mills, even though she had a very tiny baby.

In the early 1860s, they moved slightly out of the city centre to Ardwick, and lived on William Street. This was close to Ancoats goods yard. John died there in 1863, aged three. They shared a house with another small family - Ellen Metcalfe and her two little children - and as the older boys left school, the family took boarders. It was crowded.

Let’s not imagine that George Ellis was a nice man, or a temperate man. He was a shit: an alcoholic and a bully, with a reputation for violence. He gave up steady work in around 1866, and made money breeding dogs. He had multiple convictions for stealing animals. In February 1871, he went to prison for a month for stealing a dog. He appears to have served a longer sentence than he was supposed to, perhaps because of bad behaviour,, and came out in June. He kicked Catherine about, but this was nothing unusual in the area and unlike Maria West, Catherine didn’t seem to have much support from her neighbours. Nobody had any money, everyone supplemented their income with petty crime. This was a community which kept its head down and its nose out of other people’s business.

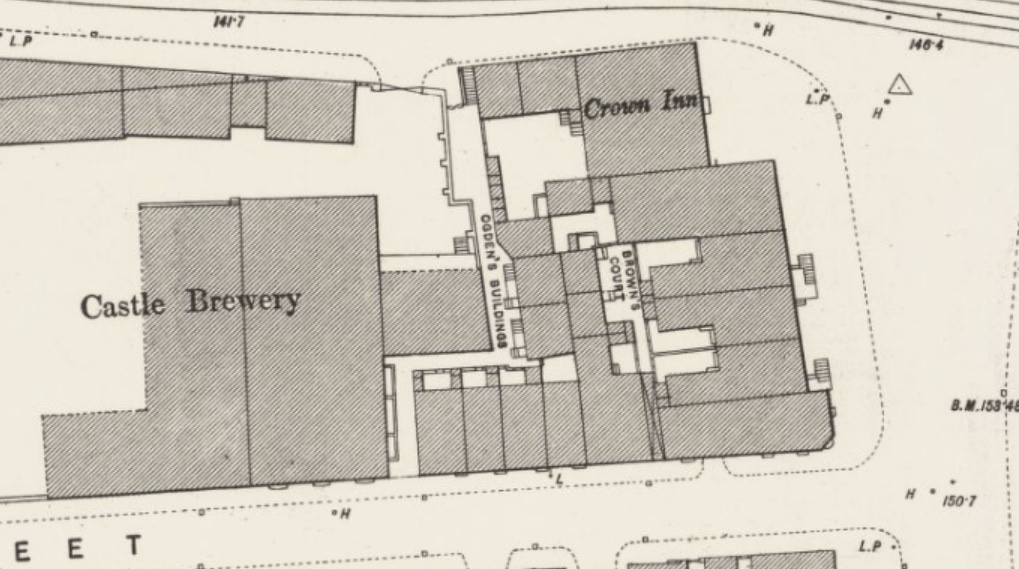

On June 13th 1871, a Tuesday, George went out on the lash. As the map above shows, there was a pub behind his house, but there were three other large inns within a few yards. He drank at the Corporation Inn, 100 yards down the road.

While he was out, Catherine had a drink with their housemate, Ellen Metcalfe. She wasn’t drunk, and Ellen went out at 9:30pm leaving Catherine to watch over her little children. George came home around 10:30pm. He was very drunk and in a foul mood. He went up to bed, discovered that the bed was unmade (presumably because Catherine hadn’t finished drying the sheets) and they had a long argument. Around midnight, he attacked her.

He picked her up, and threw her out of the bedroom window, almost four metres from the ground.

The neighbours heard her shriek

“No George, don’t put me through the window! I shall be killed!”

and they heard her fall, heard her land, and heard her moans, but they did nothing to help. They later made excuses about not wanting to get involved, not wanting to upset their ‘master’… They left her lying in the road.

George closed the window, left his house through the back door, and went back to the pub.

A little while later - fifteen minutes or so - a young railway porter passed Catherine lying in the road and she asked him to help her. He carried her into the house and laid her on the sofa, then left. Ellen Metcalfe found her there when she came in at 1am. George and his friend came in about half an hour later, followed by their eldest son. George told his friend that Catherine was drunk, and forced her upstairs. She came back down in the morning, and laid back down on the sofa.

And there, as my inquest judgements often say, Catherine languished and lingered. And now her neighbours crowded in to the house to look after her, after ignoring her dying in the road. A neighbour sent for a doctor and a priest, and the doctor (who was not actually a qualified doctor) gave her some medicine.

George came in to the house on the Thursday evening, drunk again and belligerent, and sat down heavily on Catherine’s chest. One of the neighbours told him that Catherine needed her medicine. He said she needed a good thrashing. Another neighbour said she knew George had thrown Catherine out of the window and he didn’t exactly deny it. First he claimed he was in the pub, but his son Thomas (17) had been at home that night and contradicted him. George hit Thomas and then said:

“No one saw me do it, so I have you licked”

He did not give a single solitary fuck. He ordered all the women out of the house and, terrified of him, they left.

The doctor who was not a doctor became thoroughly alarmed when he visited the house again, and made an order for her to go to the hospital. Catherine was finally removed to Manchester infirmary on Friday 16th June, after two days of lying on the sofa. She was taken away when George was out. When he came home and found her gone, he swore loudly about her having gone to the infirmary, instead of dying at home.

She died on Sunday 18th, but, in her dying state made no comment about how she’d been injured. Her death was caused by peritonitis: her bladder had ruptured, but she also had finger-mark bruises on her elbow.

George was arrested, although not for the murder of his wife. The night before Catherine died, Ellen went to find him and found him asleep in a beerhouse. She woke him up and told him Catherine was dying. George said she was ‘too hard’ to die. His eldest son was present and commented that George had often threatened to kill her and now he’d finally done it. On Sunday, after Catherine died, George was still at liberty. He went home drunk, and kicked off outside his house, saying he wanted his wife’s ‘club money’. Most poor people paid into burial clubs, a form of insurance which enabled a decent funeral. He was arrested for drunk and disorderly behaviour, and after being taken into custody, was charged with murder.

He appeared in the magistrate’s court on 23rd June, and opted to question some of the witnesses himself. He accused Ellen Metcalfe of being a prostitute (she probably was) and claimed the man who saw him go out after Catherine fell from the window was ‘mistaken on several points, but I don’t wish to bother him’.

At the close, he asked for a pint of beer, and seemed surprised that he was not allowed to drink while remanded. He reappeared a week later, and more evidence was given about the frequent beatings he gave Catherine, the way he drank all evening and came home and sexually assaulted her. He claimed the women giving evidence did so through spite, that they should mind their own business.

But then the officer who arrested him told the court how George said he would get ‘five years for this, but I don’t care if I swing.’

George tried to tell the court that Catherine was a habitual drunkard, always hammered. His eldest son claimed he’d given her three gills (less than a pint) of beer that evening, which hardly seems enough to cause falling out of a window. George then got his friend to claim that Catherine had been falling down drunk on the day she fell through a window. This friend was absolutely blind drunk at the time, hadn’t noticed George leave the pub, got his days mixed up and testified about the wrong date.

It all seems to have been so much bollocks, a half-assed attempt to build a defence.

George was sent for trial for murder, without bail. He stood trial in Manchester Assize court on 28th July 1871. Again, his only defence was the testimony of his (self-confessed) very drunk friend, and his son, who at twenty already had a long petty criminal record. The jury took half an hour to find him guilty of murder.

George was shook.

“I should have this to say. I am innocent, so help me God, I am innocent… I have been ruined by a drunken wife!”

But the black cap went on, and judge pronounced the death sentence and George, struggling and shouting about the evidence, went to the condemned cell at Salford jail to wait for the inevitable.

George had numerous run-ins with the magistrates, and generally talked himself out of trouble. He really believed that he would get away with killing his wife; that Catherine’s drunkeness (which was hardly proven) would show that she must have fallen from the window by accident. He hoped that his friend, his incredibly drunk friend, would prove that George had never left the pub. He got his son to testify about how his mother was a sot. The fact his son did suggests Catherine got grief from more than one man in the family.

And even though he was heard arguing with his wife, and even though she was heard screaming at him not to throw her out of the window, and even though he was seen leaving the house straight afterwards, he genuinely believed that as nobody saw him do it, he would be fine.

George should have been executed in August, but was reprieved within a few days of the trial. It was fair enough - she could have fallen, she could have tripped, he may not have meant to kill her. I mean, he picked her up and threw her out from a window more than three and a half metres up, but nobody actually saw it happened and her death some days later, from peritonitis rather than busting her head open, was a bit…you know…slow.

It was said that he had become penitent on death row, dropped his callous indifference. But then bullies usually do repent when faced with justice.

On 26th September, he went to Pentonville. On 30th May 1872, he was transferred to Portland in Dorset. I believe he died there in the 1890s, although I cannot find a death registry entry. His sons, who were 20, 17 and 14 when their mother was murdered, remained in Manchester.

Catherine Ellis

(1820-1871)