At the beginning of October, I switched to full time study and thanks to a combination of DEADLINES, I’ve hardly surfaced since. In AMAZING news, the Foundling Hospital’s digital archive of foundlings is now online. There are thousands of records to explore.

Last time, I left you in the County Hall at Nottingham in late July 1844, where William Saville had just been sentenced to death. Let’s go back to the condemned cell.

William Saville was sentenced to death, and this presented Nottingham with a challenge. We like to imagine that people were hanged left, right and centre in the nineteenth century, but it was actually a relatively rare event outside of London. It was considered inhumane to make people wait long periods of time for execution: a couple of weeks considered enough time to allow any post-trial processes to conclude, let the prisoner say their goodbyes and atone. William was sentenced on 25th July. His execution was fixed for 7th August.

Nobody had been executed at Nottingham for two and a half years. Until 1817, executions took place outside the city centre, where there was plenty of space. Daniel Diggle was executed at Shire Hall, but then the city went back to executing its criminals on the edge of Sherwood Forest at Gallows Hill. From 1832, all felons were executed at Shire Hall. It was arranged for William to be hanged on a scaffold outside Shire Hall, now the National Justice Museum. High Pavement is not particularly wide, and did not lend itself to the spectacle of a public hanging. The arrangements were in the hands of the city sheriff.

People loved a hanging. Even after executions were made private in the 1870s, people would still cluster to the prisons when they knew they were taking place. And on the morning of 7th August, the crowd began to assemble very early indeed: High Pavement was full by 5:30am. An execution crowd was a weird, festive mass: people selling food, drink, pamphlets about the crime, ballads about the crime. People came from miles to see the show, brief as it was. Black humour, scuffles and vulgarity were normal, as was pickpocketing. The middle-class observers were disgusted.

Executions were a morning event. William slept fitfully and was characteristically most concerned with what he would wear to die - he wanted to wear white trousers, but was persuaded to wear black. At 7:30am, William was led to the Grand Jury room at Shire Hall to listen to a religious service and be prepared. His legs were put into irons, his necktie removed and shirt unbutton, and then he was pinioned, with his arms tied behind his back. Only then was he led out to face the gallows that had been built on the steps of County Hall…and the crowd.

William went outside at 8am and was dead at 8:03am. This was not a drawn out spectacle. His legs shook for two minutes, and the crowd cheered his death. After an hour, he was cut down and taken back into Shire Hall for the formality of an inquest before burial within the prison grounds.

There were thousands of people crushed down High Pavement, many of whom had been there since dawn. People fainted and were carried out to the end of the road numerous times. But they waited because they wanted to see William die.

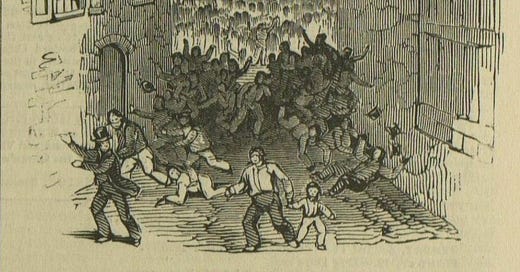

Once he died, the dam burst. The excitement was over, and people could no longer tolerate the crowd. But there was nowhere for the crowd to go: the inhabitants of High Pavement had closed their doors and gates, anticipating the number of people who would attend. Hundreds of people were forced down Malin Hill, falling, crushing… dying.

The Mayor of Nottingham had watched the execution out of his window, and was horrified. He waved a handkerchief and a stick out of his window to no avail: there were just too many people. Garner’s Hill filled up with confused, dazed people, tripping and falling.

The Mayor took charge, opening up a warehouse to act as a makeshift hospital and opening his yard as a deadhouse. Other Nottingham elites opened up their warehouses, lent carts and drays to moved people to the hospital, and slowly, the streets were cleared of broken, dying bodies.

The streets were promptly refilled by frantic relatives, searching for loved ones. Rumours of death were everywhere, and eventually the Mayor had a list with descriptions of the dead displayed at the police station and hospital. Nineteen people were required to remain in hospital, and another seventeen admitted to the dispensary. Countless others were sent home to recover, or in a position to have medical care delivered at home.

The first inquests were held that very evening, with the jury sitting in the upper storey of the police station hall while the first eight bodies were displayed in the lower storey. Another huge crowd assembled outside for the event. The families of the first eight identified the bodies: grandchildren, children, spouses and siblings, all with the same story. They had last seen them alive that morning, when they said they were going to the execution. The Mayor told each family that they would be helped in getting the body of their loved one home after the inquest. Stories of heroics began to emerge. James Fisher was twenty-two, and had saved two lives by pulling men up who had fallen in the crush. He died while trying to save a third.

The coroner and his jury then walked to view the next three bodies, before sitting in the Hospital’s governor room to hear more identifying evidence. Two sets of siblings had died in the crush - Mary and Thomas Eastthorpe, and Mary Stevenson and Eliza Smithurst. The inquest then adjourned.

It recommenced at 8am on Friday 9th August at the Town Hall. This time, the witnesses were people who had seen the crush, from their upper windows. The crisis had been rumoured to have been started on purpose, by thieves hoping to get some cash in the confusion, but there was no evidence for that. The road was simply too narrow to accomodate the crowd, who fell in vast numbers, crushing each other, suffocating, breaking bones. Those who fell were trampled, as people desperately tried to reach safety. One man told the story of a woman who was trampled for twenty minutes: he was sure the crowd could not help but stand on her and didn’t even register that she was there. The same man said he had seen no police about, but he did not believe they could have prevented the crush.

One man who survived the crush gave evidence, explaining that the motion of the crowd gave him no way of escaping, and he fell at Garner’s Hill on top of a mass of two hundred people.

The police inspector in charge gave evidence. He had also been trapped, for more than an hour, and said this was the first execution he had attended without javelin men. Javelin men attended executions as a kind of sherrif’s guard, but did not attend William Saville’s.

The jury refused to return an accidental death verdict unless they were allowed to censure the authorities for their lack of care. And so a rider was appended, that the jury

“expressed their opinion that considering the extensive excitement which prevailed, sufficient precaution was not taken by the proper authorities to prevent accident.”

The inquest closed. Eleven families prepared to bury their dead.

God forbid the authorities of Nottingham take any responsibility for crowd control. They knew people would turn up, they knew they’d all squish themselves down High Pavement like sardines, and they knew they’d all have to leave. And they did nothing.

In 1832, following arson and riot at a silk mill, three men had been executed and barricades were erected after people living in High Pavement (including the vicar of St Mary’s) wrote to the sheriff expressing their concerns. Five executions took place there between 1832 and 1842, without incident. It’s not clear why William’s execution was different. There were no barriers, no javelin men to give a sense of order… and William’s crime was awfully, morbidly fascinating.

The deadly crush at his execution went down in history, emblematic of the awful working classes and their obsession with the macabre, as though the windows of High Pavement weren’t full of higher class people watching eagerly. But nobody seems to care who they were: most web pages on the case claim there were only twelve victims, when there were thirteen. Their names are absent, unimportant.

They were mostly young women and kids, people without the body mass to resist the push of twelve thousand people. Mary Stevenson left two small children orphaned. Mary Easthorpe had permission to attend the execution: her little brother Thomas did not and tagged along, as little brothers do. Eliza Shuttleworth begged her mother to be allowed to go, even promising not to have breakfast if she was allowed (saving her mum a penny). Mellicent Shaw walked all the way from Kimberley to watch the hanging, and the news travelled home slowly. Eliza Percival’s employer had given her the morning off to watch the execution. Thomas Watson’s parents attended the execution with him, but were separated in the crowd and they saw his lifeless body carried out. James Fisher saved three lives. John Spinks was a watchman, who broke his thigh and died several days later.

William Saville was responsible, directly and indirectly, for the death of nineteen people. A dire legacy.

Mary Stevenson (33), Mary Percival (13), Mellicent Shaw (19), Eliza Smithurst (19), James Marshall (14), Mary Easthorpe (14), Thomas Easthorpe (9),

Eliza Hannah Shuttleworth (12), James Fisher (22), John Bedwell (14),

Hannah Smedley (16), Thomas Watson (14), John Spinks (74)

Another powerful article.

The fascination with executions is really quite bizarre and somewhat alien to me. I cannot fathom why Id ever attend one other than for academic purposes. Why do these events draw people and did people back then go for similar reasons?

It is also worth pondering the structures and policies regarding executions. It seems they were unprepared. It also seems that the details surrounding William's crimes brought more people as opposed to those of the other people who were executed.

JFK.