I have dared have a weekday off, so this is a scheduled post. I mentioned this case briefly on social media, because the outcome shocked me. I wasn’t going to write it up - it’s shorter than my usual stories because there’s not much information available - but my sense of outrage hasn’t lessened in the past six weeks. So, to Bilston in Staffordshire, 1843.

Bilston in the 1840s was a small town surrounded by a sprawling mass of coal mines and canals. The parishes on the outskirts of Wolverhampton ran into each other, mines, quarries, ironworks and railways, clusters of houses built to house the employees of a particular works. There were men here, men born there, men who came to find work from further afield, men accompanying canal boats to drop off and collect heavy goods. These men married in their mid-twenties, but before they married, they entertained themselves. Some stole, some drank, some fought, and some… well, you’ll see.

Mary Wild came to Bilston in the summer of 1843, when she was seventeen. It’s not clear where she came from. In her own words, she lost her former job in service in July and went on the streets. Then, as now, there was safety in numbers when it came to sex work and she went around with another girl called Ann Willis. Ann was three or four years older than Mary, and more experienced. They lodged together at the Crown on Bridge Street in Bilston.

On 29th November, she went to Wolverhampton with Ann. They bumped into five young men from Bilston when they were there: Samuel Fellows, Robert Purslow, John Perry, Daniel Webb and Thomas Haynes. Ann and Mary knew the men, they had seen them as clients in the past, although Mary had not yet been with John Perry. All the men were single, and in their late teens and early twenties. They were all a bit rough. The women joined the men to drink together, although Ann later claimed that neither of the women were drunk.

Five hours later, the group made their way home along the turnpike road. This appears to have been modern Wellington Road. As they got to the area that is now Hadley Road, the five men began to negotiate the women’s services for the night. Daniel Webb wanted Ann, but she said no and he punched her. Thomas Haynes then proposed that she go with him instead, and Ann agreed. They left Mary with the four other men. The four drunk men who’d already assaulted Ann.

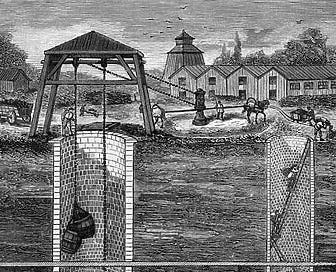

Once Ann and Thomas had left, the other men tried to persuade Mary to have sex with all of them, with Daniel Webb being particularly persistant. This was a bit much for Mary, who said no. They got violent, they punched her, threatened to throw her down a mineshaft. But she continued to say no. They abused her until she was unable to see anymore, and pulled her underwear off.

Then they seized her round the waist and threw her down a mineshaft.

The mineshaft was twenty-five metres deep.

Daniel Webb and Robert Purslow ran away, but Samuel Fellows and John Perry went to fetch help - Mary was unconscious, so perhaps they assumed she was dead. They could have left her there, nobody would have found her unless Ann went to the police, but they didn’t. A nearby shoemaker helped get her out of the pit, and, with the guidance of Samuel and John, took her home. They arrived at 1:30am, by which time Ann and Thomas Haynes had finished their business.

Mary’s injuries were horrific. She had a head wound, two nasty wounds on one leg, a compound thigh fracture and a crushed pelvis. Some bone from her pelvis pierced her peritoneum, causing an infection. She lingered for two weeks, dying around 14th December. She was buried on the 15th and her inquest was held on the 19th December.

However, Mary had regained consciousness and was lucid during the first week of her protracted dying. She made a statement explaining what had happened, in the presence of the four men accused of throwing her down the well. One can only imagine them at her bedside, in the same bed that Daniel, Robert and Samuel had all used her services, standing there as she explained what they’d done to her on oath.

The inquest found a verdict of wilful murder against the four men, and they were committed to an assize trial. The Staffordshire winter assize was held about ten days later. On 30th December, the four men were tried for murder. Their defence was threefold: why wouldn’t they just rape her? Why go to the trouble of chucking her down a mineshaft? Secondly, how could they be sure she’d been thrown at all? It was dark, maybe she fell down by accident: two of the men tried to save her, something they surely wouldn’t have done if they’d wanted her dead. And finally, Mary testified that one of the men had left the scene before she’d been thrown down the shaft, but she didn’t know which one because she couldn’t see. With this doubt about who had actually been present, the men were acquitted of murder.

They were immediately rearrested and tried on a charge of “assault with intent to commit rape”. Their defence tried to get this charge thrown out on account of double jeopardy: they’d already been tried and acquitted. However, this charge was about what happened before they threw her down the pit, a separate event as far as the judge was concerned. The jury took ten minutes to find all four men guilty. The judge told them what had happened on that awful night was between them and their conscience, and sentenced them as harshly as the law permitted.

Eighteen months each with hard labour.

If Mary had died at the scene, as the four men clearly intended, then no murder charge would have been raised. The men would have said she fell in by accident, and Mary would not have been able to contradict them. Instead, in agony, she faced her four attackers and gave a statement.

There was power in a deathbed statement, admissable in court because it was believed the dying had no incentive to lie. Mary’s words could have condemned her attackers to death, but the court was not quite prepared to allow it to go that far.

The four men were ‘disorderly’ while imprisoned, and were released in June 1845. They left Bilston, although none of them moved very far away. All four married within a few years. Daniel Webb remained violent towards women, beating up the mother of his child when she accused him of paying maintenance using counterfeit money, but he stayed alive. All four had relatively normal lives.

Ann Willis, Mary’s friend, did not. She died in 1847, aged twenty-six. She never married. The life of prostitutes, as my friend Claire has described in her book, could be nasty, brutal and short.

We know almost nothing about Mary. We know she was seventeen, and that she was probably local - there was a family called Wild in Bilston - and that she felt her best way of making a living was through prostitution. We don’t know when she was born, or what her real name was - some sources have her as Mary Jane, others as Mary Ann, some as just Mary.

We know that she was brave, that she said no to these four violent men even as they beat her up and tried to force her into a gang rape. We know that she was brave, and gave a statement through her pain. We know that she was brave, as she gave this statement while her attackers stood by.

We know that she was brave.

Mary Wild

(1825-1843)

Thank you for telling this moving story about a brave victim. To modern eyes that they would offer such a defense is shocking, but that it was offered perhaps suggests that it was not that uncommon and that it did sometimes work.